Joost was strongly influenced by Hergé's Tintin adventures, and his style is similarly precise and clear, meticulously crafted and elegantly coloured by watercolour. Yet his content could not be further from the innocent Tintin, taking it's cue across the Atlantic from the adult content of the underground American comics scene, and artists like Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb.

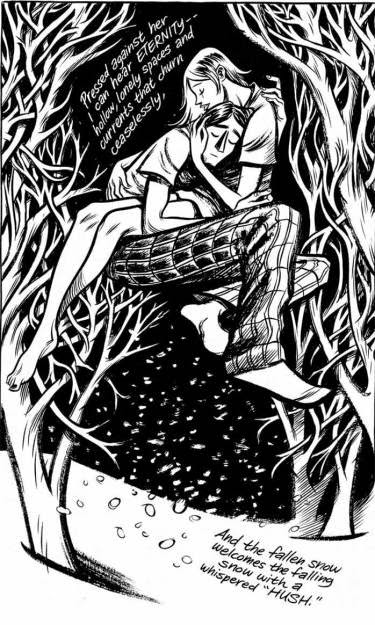

Joost Swart's most popular creation was Jojo de Pojo, a lad sporting a quiff and plus-fours, yet who, rather than save the world from crime and evil, indulges in activities Tintin never even dream of. His audience, brought up as boy scouts, and now young adults in the seventies, experimenting with narcotics, alcohol and sex, would have appreciated the artist struggling with complexities that they encountered in their everyday lives.

Swart is a renaissance man, and is a graphic designer and architect, has designed furniture, murals and stained glass windows. He designed a theatre in Haarlem (his hometown), and designed the interiors of the Hergé Museum in Brussels. He founded a publishing house in the eighties and in the nineties instigated the Comics Event held in Haarlem. Chris Ware also writes in his introduction that, when he visited the artists studio, he had just finished designs from pastries for his local patisserie, and how he faxed him a beautifully drawn map showing how to get to the studio. This charming and innocent approach seems to underpin much of his work, and he operates at the personal level, getting involved in projects close to his heart (and his home), rather than the one with the largest pay-cheque.

This small book will introduce one of the greats of European comics to a new audience, bringing together strips that were published over 40 years ago, in obscure Dutch magazines, and re-presenting and translating them for fans of comic books the world over.