In a second hand book shop in Eton High Street I found a

1927 edition of Frans Masereel’s third woodcut novel, ‘Die Sonne’.

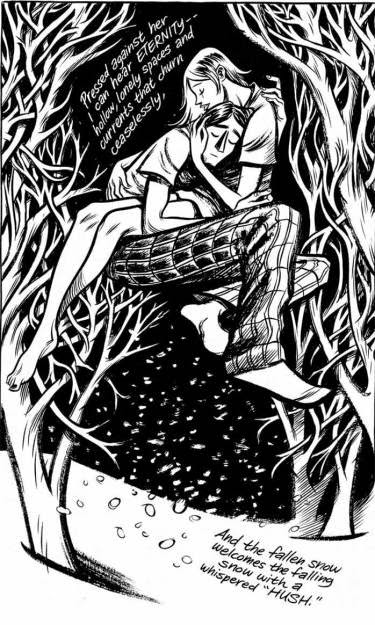

Originally published in 1919, Masereel creates a silent

narrative in black and white woodcuts, each 80 x 99mm and packed with detail.

Die Sonne starts with an artist falling asleep at his window, with a blazing

sun in the sky. As he lies with his head on the table, a little man emerges

from the sleeping man, and tries to jump towards the sun, arms outstretched. He

tumbles to the ground, and is surrounded by a crowd of people: he points to the

sun, and the crowd lift their hands in shock, or laugh at him. As he

rushes up a staircase, towards the light the crowd follow him, shaking umbrellas

and fists, horrified expressions on their faces.

The crowds are unable to suppress the little man, and

despite throwing him in jail, distracting him with sex, alcohol, knowledge and

religion, he continues, like a flower climbing towards the sun.

Almost every panel contains the sun, and even panels illustrating

the ‘distractions’, a light reoccurs as a motif, emanating from a book,

Christ’s halo and the candles in the church, the lamp burning outside the

brothel, the fireplace and a lighthouse.

Masereel was a staunch socialist, and before his woodcut novels,

he worked on socialist magazines, contributing satirical woodcuts to illustrate

left wing articles. During the first world war he refused to fight, and worked

as an interpreter for ambulance crews. Masereel was born in Flanders, and

aesthetically his work is close to the German expressionists (George Grotz was

a close friend), but his work differs from much expressionism, as the message

was more political, and his medium reflects his desire to reach the masses,

using mass media, rejecting the narrow confines of the art gallery and

bourgeois connotations of canvas painting.

His work is more closely related to the cartoon, and with an

80 x 99mm space for his work, his characters, drawn with a few cuts of his

tools, are caricatures, by necessity of the medium. The crowds are full of

portly businessmen in top hats and umbrellas, the people gesticulate like

actors conveying private emotions to a large audience, or a singer performing.

When Masereel was creating ‘Die Sonne’ cartoons were already

quite sophisticated, and in America George Herriman was already writing his

Krazy Kat strip. Dialogue was already integrated into comics, and literacy,

even among working classes, was relatively high in Europe. So, why did he

choose to make wordless narratives?

The silent film was at its height at this time, with their

simple narratives and exaggerated gestures, Masereel’s work echoes this medium.

The stark black and white of his woodcuts also is reminiscent of the strong

lighting in ‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’ (1920), and other German expressionist

films.

Masereel had a training as a painter and graphic artist, and

these media influenced his work strongly, each image standing on its own as a

work of art. Hergé took up to 64 pages to tell his stories, each page with up

to 16 panels. Masereel took 63 images to tell the story of Die Sonne, using

only two or three panels per scene. Each panel works like a painting, with many

different elements contained, and, as with other contemporary painters, he did

not feel the need for the written word.

The lack of words keeps the meaning of the text vague, and

the interpretation of the story is left to the read. What is the sun? Is it

God, love, justice, inspiration or freedom? Many socialist artists have been

overly didactic in their work, but Masereel’s work remains relevant and alive

today, as the reader can apply their own meaning to the narrative.

Masereel has been an enormous influence on a whole

generation of comic book authors and artists. Art Spielgelmann cited him as a

major influence, as did Will Eisner.

The book is small in size, just a little larger than A6,

printed on soft paper with a yellow tinge (although this may be due to its

age). The images are printed with a strong, opaque black, and leave a

satisfying imprint, visible on the reverse of the page.

The works were printed in large quantities, up to 100,000 of

each, so many copies should still be in circulation. There are also many new

editions available, so you should be able to find copies of all of his works.